Chapter 2: Legislation for the Protection, Promotion, and Enforcement of Disability Rights in Bolivia

Official discrimination against people with disabilities is still a reality, in the workplace, in schools, in access to the healthcare system and in access to government services. Societal discrimination against people with disabilities has confined many of them to their homes from an early age, thereby limiting their integration into society.

The People with Disabilities Act (Law 1678) allows tax-free imports for orthopaedic devices, stipulates a 50% discount on public transport and promotes the teaching of sign language and Braille.

This study has also found that the law itself is discriminatory against people with disabilities in certain cases. Disability has not become a subject of public interest, nor has the government prioritized its inclusion in the governmental agenda or in that of civil society. Policy-makers, authorities, government officials, and social actors in general are unaware of improvements in relevant laws and regulations; in other words, the regulations are not enforced at all. Generally, it has been treated as a private issue, confined to inner family spaces. It has not moved beyond a philanthropic approach that has been in effect for decades, based on notions of compassion and welfare. Actions in favour of people with disabilities have been considered part of the work of public charity, Christian solidarity and voluntary efforts, resources which are insufficient and do not provide solutions that address the magnitude of the problem, limiting it instead to the private and clandestine margins of society.

In addition to the National Council for People with Disabilities (C.O.N.A.L.P.E.D.I.)—whose mission is to promote and foster joint operations with different sectors of society for the adherence to and enforcement of Supreme Decree Number 24807, based on respect for differences, tolerance and non-discrimination—there are other organizations with a disability rights mandate established by the Bolivian government, such as the Departmental Committee for People with Disabilities, the Christian Fraternity for the Sick and Disabled, the Federation of Integrated Wheelchair Sports, The Bolivian Federation for the Deaf, The Bolivian Association of Parents of Children and Adolescents with Mental Handicaps, and the Bolivian Federation for the Blind and Deaf. All of these organizations are part of the Bolivian Confederation of Persons with Disabilities.

The results of this study indicate that the Committee has included disability as one of the human rights concerns covered by its mandate; however, some organizations are inactive in most of the country. Most public buildings and private companies are not wheelchair accessible, and, as the Permanent Assembly acknowledges, “in general, special services and infrastructure to facilitate the circulation of people with disabilities do not exist. The lack of resources makes their full implementation impossible.”

The study also showed that in Bolivia, people with disabilities live in constant exclusion and inequality, as victims of discrimination in different processes of socio-economic development in the country, violating their fundamental human rights on a daily basis in their social settings, in their families and in society as a whole. This situation is further aggravated by the poverty in which the majority of people with disabilities live.

The extensive national and international legislation that protects this important group has, for many years, both on paper and in practice, been completely insufficient.

2.1 National Legal Framework of Disability Rights

2.1.1 Legislative Framework

Legislation includes the regulations established in Law 1678, the international conventions and agreements ratified by the Bolivian government, and regulations that organize the structure and the functioning of the country. Especially relevant as an ethical, philosophical and guiding framework for the Plan, are the 1993 United Nations Standard Rules, the Salamanca Declaration issued at the Global Conference on Special Needs: Access and Quality, the United Nations Convention and the Spanish-American declaration of the Year of the Disabled.

The socio-economic situation, system of government and Bolivian society in general demand an active role of the state with respect to disability, as well as the active participation of civil society, representative disability organizations, N.G.O.s, social organizations, volunteer groups, the private sector and social and political actors more broadly.

Regionally, there is a struggle, including social protests and demonstrations, to develop policies and strategies so that both state actors and social actors in general can responsibly contribute to the development of a more inclusive, fair and humane society: a society that respects and protects the rights of people with disabilities, their ethnicity and their gender, thus broadening the opportunities available to people with disabilities in a context of fairness in all aspects of economic, cultural, social and political life, allowing them to develop their abilities, enjoy greater social protection, and broaden and strengthen their social participation and inclusion. There is no constitutional definition of disability in Bolivian law; however, there is a legal definition in the framework of the People with Disabilities Act (Law 1678), which defines disability as the following: Any restriction or lack, resulting from an impairment, of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being.

The definition of Law 1678 is sufficiently broad to include those people who would not traditionally be considered to have a disability, including those with intellectual and mental disabilities.

The Bolivian constitution includes statutes that guarantee human rights and freedoms for its citizens, rights which apply to all citizens. People with disabilities are expected to enjoy these rights equally with the rest of society.

Article 71 of the constitution prohibits discrimination on grounds of disability, yet the majority of people with disabilities in Bolivia experience inequality, exclusion and poverty. They are victims of discrimination in different spheres of social life, they do not have equal access to opportunities, and they are subject to a permanent violation of their rights by cultural constructs based on internalization, depersonalization and the denial of others and of their dignity. Cultural constructs are the main factor affecting disability rights. The lack of information and knowledge leads to stereotypes, prejudices, beliefs based on a social system that values “perfection”, and “beauty”, under highly exclusive conventional parameters.

Cultural constructs have created segregated spaces for the development of people with disabilities, and they have determined a priori a limited range of opportunities for people with disabilities that, using parameters not intended for people with disabilities, supposedly cover their basic needs. Opportunities for people without disabilities are prioritized, to the extent that it seems that they are the only people that have a place in society. People with disabilities are condemned to move through spaces that are on the margins of normalcy and daily life.

Law 1678 includes statutes that prohibit discrimination against people with disabilities in several sectors, including education, the workplace, health, and the provision of services, both in the public and private sectors. Article 7 is related to health matters, article 8 is about education, article 9 prohibits discrimination in the workplace, and article 10 prohibits discrimination in access to buildings and other installations. Articles 11, 12, and 13 address indirect discrimination in such spheres as television programs and telephone and postal services.

The current challenge is to implement the law in the interest of accelerating processes of equality and the equalization of opportunities for this important group.

2.1.2 Governmental Organizations Working with People with Disabilities

The National Council for People with Disabilities, called C.O.N.A.L.P.E.D.I., was formed by virtue of Chapter VI of Law 1678. Article 19 establishes the specific functions of the Council, which are to issue orders enforcing Law 1678 and to supervise their suitable application, in coordination with state, private and mixed organizations. It also seeks to improve the application of the Global Action for People with Disabilities, standard rules for the equalization of opportunities and other regulations designed to encourage the integration of people with disabilities into society. The Council also has the mandate to develop its operational regulations and the organization of the executive, for the express approval of the Ministry of Human Development by ministerial resolution.

In its mandate to guarantee that the rights and privileges of people with disabilities are upheld as established by law, the Council must coordinate with other institutions that directly bring together and work with people with disabilities.

In addition to the National Council for Persons with Disabilities, there are other bodies that have been established by the government through diverse laws.

The Departmental Committee for Persons with Disabilities has as its objective to promote and raise awareness about Law 1678 and other legislation related to the fundamental rights of people with disabilities, and to establish norms and procedures for the enforcement of this law.

This work is carried out in seminars, conferences, workshops, etc., which have not been sufficient to reach all the people that benefit from the law nor those upon whom it confers obligations with respect to the protection and support of people with disabilities.

2.1.3 Poverty and Disability

Employment

There is no labour law that takes into account the labour needs of people with disabilities, although the General Labour Law regulates labour laws for all Bolivian citizens to an extent. The law could be interpreted to contribute to the economic marginalization of people with disabilities, as it does not address the employment of people with disabilities, which is an issue that demands special attention. The law does not recognize that people with disabilities face discrimination when they look for work and that they have limited opportunities in comparison with people without disabilities. The law does not include any statutes that impose obligations on employers to employ people with disabilities, thus abandoning them to the liberalization of the job market, which is strongly biased against them.

Poverty is the most extreme form of social exclusion and is directly related to unemployment, labour instability, low labour costs, precarious and informal jobs and low wages. In the country there is limited capacity for job creation. Large enterprises generate 8.7% of employment, compared to the small and medium-sized companies which contribute 83%, the majority of which are in the informal sector, demonstrating the structural limitations for generating stable employment.

In addition to the limitations of the labour market, with an unemployment rate of 13.9% and with a forced trend towards self-employment and under-employment, employers and workers also have prejudices, stereotypes and discriminatory practices with respect to people with disabilities.

Working constitutes a right because it allows people to generate income in order to access goods and services for personal and family subsistence and it permits a life with dignity. It generates the conditions for normal social engagement, the development of human potential and personal autonomy and allows one to contribute to society. The cultural meanings of work and the material and personal outcomes of labour insertion are of even greater importance for people with disabilities, because it channels their creative contributions, of economic and social utility, and also allows their social inclusion.

Supreme Decree 27477 regulates and protects the incorporation, advancement and labour stability of people with disabilities, establishing their priority employment status and stating that of all their staff, public institutions must hire an average of 4% of workers with disabilities, and they must create the conditions for these workers to perform their tasks.

Some factors that limit labour insertion are:

- A limited formal labour market that is covered by labour legislation.

- The largest contribution to job creation comes from the family and micro-enterprise sector, generally in the informal sector.

- The lack of ongoing training and job-entrance programs, resulting in the insufficient development of labour skills for people with disabilities.

- The stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes held by employers and workers.

- Limited family support for people with disabilities to encourage their inclusion in the labour market.

- The perceptions of people with disabilities, their immediate families and their social environment.

Current economic conditions have caused an increasing deterioration in the labour market, including the widespread growth of precarious jobs, both in the formal and informal sectors, with labour conditions that do not meet the norms of industrial and occupational safety, for children, adolescents and adults. These working conditions thus put both health and job security at risk.

There are not many financial sanctions or possible criminal charges (Article 26) for instances in which these laws are not enforced. To date, there have not been any cases brought to court under this law.

Accessibility

“States must recognize the global importance of providing access as a component of achieving equal opportunities in all spheres of society. For people with disabilities of any type, countries must:

- Establish plans of action to make the physical environment accessible.

- Adopt measures to guarantee access to information and communication.” (Article 5. Standard Rules. U.N.)

The accessibility of public spaces is an essential characteristic of the built physical environment that makes transit through and social use of such spaces possible, allowing people with disabilities to participate in the social, cultural, educational, economic and political activities for which such public spaces were constructed.

Accessibility varies according to the type of disability, with different requirements for physical, auditory and visual accessibility. The state of technological development of the country is limited; the few initiatives in the field have tended to provide technical help for physical disabilities, including a wheelchair factory and a few small prosthetic companies.

Poverty invites the common alternative of donations, where the systems of distribution are not the most effective, and the lack of a donation policy and inter-institutional coordination lead to these being managed within a welfare framework, with mechanisms that exclude people with real needs, creating negative effects and disincentives for national industry.

On the other hand, current societal dynamics demand transit as a service and a basic necessity, which is not designed to meet the basic needs of persons with disabilities. Vehicles, traffic regulations, urban design, and local culture make transit difficult for persons with disabilities, who have great difficulties getting to their places of work, education and health care, and in carrying out their basic social activities. Vehicles are ill-adapted and make the regular use of transportation difficult, in addition to the insensitivity of public transit drivers who refuse to transport persons with disabilities, putting them in difficult situations and exposing them to negative treatment. The challenges vary according to the type of disability, and it is worse for children and the elderly.

With the development of the information and knowledge society, barriers grow and there is a risk of even greater exclusion based on the dual condition of disability, which already puts one at a disadvantage, and the underdevelopment and poverty of the country, which makes accessing information and knowledge very difficult. Information and knowledge technologies are essential in the current context. They are an important means with which to reduce the gaps in communication, information and knowledge, and they can contribute to the elimination of social barriers. People with physical, hearing or intellectual disabilities have found that computers provide opportunities to learn, work, and be part of society. These information systems are not accessible for people living in poverty conditions, but mechanisms could be created to facilitate access for men and women with disabilities.

The National Policy Project on persons with disabilities indicates that persons with disabilities establish a legislative framework with which access problems will be addressed. Article 5 of the project states that it is equally important to recognize what constitutes access problems and to achieve equal opportunities in all spheres of society, including:

- Environment (for example, buildings and construction pose difficulties for physical access to public buildings).

- Communication (for example, electronic and print communications are generally inaccessible for people with visual, hearing or intellectual disabilities).

- Social (for example, cultural attitudes and practices rooted in the beliefs, taboos, rites of passage or religion create almost unsurpassable barriers for the participation of people with disabilities in social life and cultural activities).

- Economic (for example, barriers that prevent persons with disabilities from fully participating in employment, commerce and access to loans; many people with disabilities live in extreme poverty.)

The legislative framework of Law 1678 establishes a series of conditions related to access issues for persons with disabilities in Bolivia, including the following:

Chapter III of Law 1678—The Rights and Privileges of Persons with Disabilities—addresses issues of disability in a number of sections. However, the most efficient way to implement the legislation is to address access issues, the statutes that are outlined along with the sections with notes on the statutes and the structures where they must be applied.

In relation to employment, Article 9(d) of Law 1678 grants, in coordination with departmental labour boards, priority attention to all labour problems of people with disabilities, with the responsibility to apply financial sanctions against those who discriminate against people with disabilities in matters of employment.

Article 13 establishes as a priority the elimination of physical barriers in new urban and architectural constructions and the modification of existing ones, partially or wholly replacing the elements necessary to create conditions of access for persons with disabilities.

With respect to access and mobility, Article 13 states that persons with disabilities have the right to a barrier-free environment such that they can access buildings, highways and other social services, and the support services and other equipment necessary to promote their mobility. Article 13 (a) the elimination of urban, physical barriers on streets and in public places, (b) the elimination of architectural barriers in both public and private buildings used by the public, (c) the priorities and time frame for adjustments required by this article with respect to urban barriers and buildings of public use will be determined in accordance with regulations outlined by the corresponding volunteer committee, within six months of enacting the law.

In addition, Article 14 (a) promotes the elimination of architectural barriers in public transport by land, air, and water of short, medium, and long distances, and the use of private means of transportation for people with disabilities. Article 14 (b) establishes that people with disabilities have the right to circulate freely and to have access to parking, and (c) encourages land, air, lake and river transport companies, whether they are public, private or mixed, to give discounts of 50% to people with severe disabilities who require an escort, when their trips are interdepartmental or inter-provincial.

With respect to communication, people with disabilities face communication barriers in terms of the amount of information they can access and their communication with other people without disabilities.

According to Article 5 of the standard rules of Law 1678, people with disabilities and when applicable, their families and advocates, must at all stages have access to complete information about their diagnosis, their rights, and available services and programs. This information must be presented in an accessible form for people with disabilities.

According to the International Convention on Human Rights, countries should develop strategies so that information and documentation services are accessible to different groups of people with disabilities. With the objective of providing access to information and written documentation for people with visual disabilities, Braille, taped recordings, material with large print and other appropriate technologies should be used. Similarly, appropriate technologies must be used to give access to oral information for people with hearing disabilities or with challenges in comprehension.

Economic

Incentives under Law 1678

Article 4 (j): To establish the coordination of private enterprises, chamber of industry, chamber of commerce, exporters and small industry, in order to place people with disabilities in different workplaces, offering special incentives for hiring people with disabilities (diplomas, plaques, etc) granted once a year in a special ceremony. Similarly, the Article promotes the creation of microenterprises by people with disabilities, with the intention that they will employ other people with disabilities.

Article 4 (k): To promote and encourage the free importation of auxiliary equipment designed for people with disabilities and to negotiate their exemption from customs duties, according to Article 22, providing they are not for-profit organizations. Also, to evaluate applications for duty exemption.

Article 4 (l): To coordinate with banking entities, second-tier banks and related entities to assist in granting loans to people with disabilities.

Article 4 (p): To create a bank of orthotics and prosthetics, with equipment for different disabilities, offering the material at subsidized rates following an evaluation of economic conditions carried out by social workers. Also, to coordinate with national and international organizations, by means of conventions, to provide incentive for and coordinate research into the use of local natural resources for the manufacturing of equipment and support services for different disabilities, obtaining and disbursing funds for this purpose, and for the creation and strengthening of national manufacturers dedicated to making this type of equipment, supportive material, orthotics and prosthetics, preferentially hiring people with disabilities for this purpose.

Education

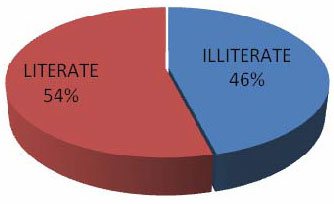

Literacy rate among people with disabilities over 5 years of age in Bolivia

States should recognize the principle of equal primary, secondary and tertiary educational opportunities for children, youth and adults with disabilities, in integrated settings. They should ensure that the education of persons with disabilities is an integral part of the educational system. (Rule 6. Education: Standard Rules, United Nations, 1993).

“[R]egular schools with [an] inclusive orientation are the most effective means of combating discriminatory attitudes, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society and achieving education for all (U.N.E.S.C.O. Salamanca Declaration and Framework for Action, 1994.)

The Bolivian education system does not provide equal education based on the respect and appreciation of children, adolescents and adults that allows their development in daily life. In addition to being a discriminatory system in several areas such as gender, ethnicity, and class, there is discrimination based on disability. Schools continue to discriminate against people with disabilities with segregationist practices, resulting in systematic isolation, which is reproduced in all spheres of life, causing different degrees of social exclusion.

There are regular schools that admit students with disabilities; however, this access is not accompanied by suitable learning environments for special needs, both because teaching staff are not trained for this type of task, and because of the widespread existence of stereotypes and prejudices in the teaching community. In effect, the educational system denies the special education needs of people with disabilities in its conception, structure, organization and management, causing academic exclusion, which is exacerbated by gender and ethnicity.

There is no data about how many children with disabilities are excluded from the educational system in the country. At the international level, it is estimated that close to 78% of the school population is excluded, due to several factors related to the availability of educational programs and their accessibility, as well as to the socio-cultural conditions of the families and their social settings.

In this complex educational context, special education has been addressed by educational policy, but with marginal attention within the system. The inclusive approach to education has not been institutionalized; although the Educational Reform Act takes it into account, educational policies that would make it viable have not been implemented. Regular school does not include special education, nor inclusive education, and is not trained to meet students’ needs based on a model of “child-centred education”, with educational spaces allowing children and youth with disabilities to develop alongside their peers, independently of their difficulties and differences, as the Conference recommended.

The first available services in Bolivia have been the public centres and institutes in each capital city, which have problems of coverage, quality, and educational achievement. Though they have addressed some issues, they do not address the different degrees of disability, and in practice, their approaches have consolidated institutionalization, with the search for “refuge”, creating a separation of education from reality and from daily family, neighbourhood and community life. Another feature is their shortcomings with respect to the quality of their services and their scarce resources, which limit the possibilities of education alongside peers and reproduce segregation in education.

Attention to disability in the educational system has been limited by the lack of specialized training. In the training of teachers and professionals, training in special education and disability is only beginning to be addressed in different centres of higher education such as the Superior Normal Institutes, and it is completely absent at the university level.

Article 8 of Supreme Decree 24807 of Law 1678 proposes:

(a) To establish strategies and norms to strengthen special education through formal and alternative education, fostering a culture of dignity and respect for the human, political and social rights of persons with disabilities.

(b) To promote the integration of children, adolescents and adults with special education needs in different levels of formal education, with equal conditions and opportunities with others, according to the principles of democratization, normalization and integration, fostering complete human development, through respect for differences, individual diversity and principles of equity, creating educational pedagogies and actions for the research, design, curricular modifications and granting of suitable means and tools.

(g) To promote the integral development of students with special education needs in the formal sphere of education according to the Educational Reform Act, including curricular adaptations. Similarly, to promote the design, development and renewal of teaching material for the development of educational processes.

Health

Health services are essential in caring for people with disabilities with respect to prevention, treatment, habilitation and rehabilitation. Disability has not been thoroughly addressed, and its care has been limited to clinical treatment, which is carried out with severe limitations due to technical and technological weaknesses and a lack of specialization.

The lack of programs for health promotion and prevention is common. Disability has generally been understood as a health problem, but not as a problem of social responsibility or a result of preventable causes, for which timely intervention could act to reduce impairments and disabilities. Currently, there are gaps in the information available to the population and to parents faced with situations of impairment; there is a lack of early diagnoses, there is a lack of integral newborn care; and there are prenatal risks and deficient public services that lead to disabilities.

Poverty is directly related to the living conditions and health of the population. The poor are most susceptible to severe malnutrition, severely malnourished children are at high risk for blindness because of vitamin A deficiencies, and at risk for complications of the motor, nervous and intellectual systems. According to the National Institute of Statistics, there are 18,995 blind people, 5,815 with multiple disabilities, and 1,200 people are deaf and blind—numbers that may be underestimated.

The W.H.O. calculates that 10% of the Bolivian population has some type of disability.

The decrease in public spending and the tax cut for hydrocarbons has limited access to health services and has notably diminished their quality. In general, the healthcare system does not have the resources needed for integral prevention, care and rehabilitation services for people with disabilities.

The decentralization of healthcare services and their municipal provision, in contexts of decreased public spending and institutional weakness, creates difficulties for the economic sustainability of secondary and tertiary care, which are most needed in caring for people with disabilities.

Health services have lost their universality and are difficult for the rural population to access, with long-standing asymmetries in services. There is a larger concentration in the urban core and almost no availability in rural areas, thus very few people use the urban services.

Some factors associated with inadequate services and their low quality include:

- There is not an integrated approach to the care of people with disabilities.

- Institutional availability continues to be insufficient and deficient.

- Human resources do not have up-to-date and specialized knowledge.

- Health workers have stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes.

- Infrastructure, equipment and supplies are insufficient and inaccessible.

- Medical and paramedic staff have limited training on the physical treatment of injured patients. Ignorance, along with cases of negligence, have been decisive factors in causing disabilities.

Furthermore, features of modern society have increased risks, such as environmental contamination and traffic accidents, which produce injuries of a different type, provoking disability. According to the W.H.O., in 2000, traffic accidents were the cause of 2.8% of deaths and disabilities in the world, and according to their projections for 2020, they may become the third largest cause of death and disability.

Other factors also stand out, such as domestic violence, social violence, and domestic accidents, which have all increased, though data is not available to measure the changes. It is important to point out that people with disabilities in Bolivia do not have complete health insurance that would cover all their rehabilitation needs. There is basic health insurance that covers all Bolivian citizens until they are 18 years of age, which only includes primary care, some laboratories, and nothing else.

Percentage of people with disabilities that are poor by type of disability:

Vivir Creciendo: An Alternative in Cochabamba

Vivir Creciendo (Live and Grow) is a program of the Univalle University Hospital, which started on October 1st, 2005. The Univalle Hospital centralized the out-patient reconditioning and rehabilitation in just one program, Vivir Creciendo, in which objectives are created, criteria are coordinated, only one file with medical records is used, and, above all, quality and caring services are provided for the benefit of patients.

The W.H.O. reports that 4.5% to 10% of the world population have some sort of disability, with 80% found in rural areas and the peripheral zones of urban areas. Physical, visual and hearing impairment are the three most frequent causes of disability, with 36%, 28% and 16% respectively in some countries (Nelson 2004, 17th edition).

These alarming and largely unknown figures further strengthen the social work that Univalle Hospital is carrying out. Because it is a tertiary-level centre that teaches and carries out research, and has the most specialities, infrastructure and cutting-edge equipment, they saw the need to integrate the Vivir Creciendo program into their services for the centralized and multidisciplinary rehabilitation of people with disabilities.