Introduction

In March 2010, Canada ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) – a document that was adopted by the UN General Assembly in December 2006 and now has 153 signatories and 112 ratifications (UNEnable website, 2012). The CRPD recognized the paradigm shift

that had already occurred within the disability community and marked a new stage in the efforts to convey disability rights to the broader public. This paradigm shift was a move

from viewing persons with disabilities as

objectsof charity, medical treatment and social protection towards viewing persons with disabilities assubjectswith rights, who are capable of claiming those rights and making decisions for their lives based on their free and informed consent as well as being active members of society (UNEnable website, 2012).

The CRPD is more than a simple declaration – it sets out several specific challenges to signatory countries concerning the monitoring and implementation of its articles. As outlined in Article 33, the UN CRPD protocol tasks countries who have ratified, with monitoring the implementation of the CRPD, and reporting to the UN thereby envisioning a process that would involve a close working relationship with national human rights institutions and other national stakeholders. Articles 4(3) and Article 33 (3) of the CRPD call specifically for including persons with disabilities at all stages of the implementation, to build the capacity of organizations serving people with disabilities and Article 8 discusses the need to raise public awareness of the paradigm shift in order to convey to elites, decision-makers and the larger public the importance of ensuring that people with disabilities are treated with dignity (UNEnable website, 2012).

The media plays an important role in the implementation of the CRPD. While individuals can come to learn about the unique issues facing people with disabilities either firsthand or in close proximity through friends and colleagues in the disability community, many people will also be influenced through some mediated form of communication, including books, film, television, radio and digital media. Mediated forms of communication have unique aspects in terms of influence that set them apart from direct contacts with persons with a disability. First, media convey a publicly-shared perception of a disability issue or a person with a disability. A person watching a newscast about the exploits of an athlete with a disability is implicitly aware that their perception of that athlete is not a personal one but one shared with a broader public. This, in turn, has certain implications as to the weight and influence of the perception. The second important difference is the agenda-setting ability of the media – primarily but not exclusively the news and information media. The media can determine not only the rank-order of issues important to the disability community within the larger hierarchical structure of issues brought to the public’s attention, but also which disability issues are highlighted. By extension, the media’s influence on setting issue priority and shared public perceptions can thereby affect the impetus and policy direction regarding people with disabilities.

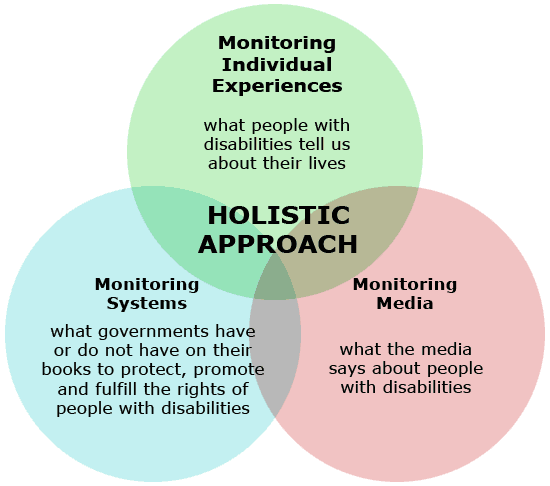

Effective media monitoring is a particular challenge posed by the CRPD. First, to reflect the principles of the CRPD, the monitoring function must involve people with disabilities and the disability community throughout the monitoring process. Second, the monitoring must be conducted by viewing and analyzing coverage of people with disabilities from the unique perspective of human rights. Examining coverage from a disability rights perspective has rarely been conducted in the past and has tended to focus primarily on framing language, as well as source and information accessibility. Third, the monitoring function must ultimately provide the disability community and those tasked with implementing the CRPD with a credible, effective means of tracking the portrayal of disability rights over time and across different regions in order to help inform members of the media as well as policy makers concerning the overall portrayal of people with disabilities and disability rights and also to be able to compare results between jurisdictions (Disability Rights Promotion International 2009). DRPI uses media monitoring as an integral part of its holistic monitoring approach.

Figure 1: Venn diagram representing the three broad areas for monitoring: monitoring systems, monitoring individual experiences and monitoring media (DRPI website, Disability Rights Monitoring).

The objective of this work was to take up this methodological challenge and to design a media monitoring methodology that meets these three criteria and to carry out this study as a pilot. If successful, stakeholder groups invested with the task of monitoring how the media within their jurisdiction covers issues pertaining to people with disabilities will have at their disposal a research strategy that will involve people with disabilities in the process of monitoring and evaluating how their rights as outlined in the CRPD are represented in the media. It will also provide them with findings that they can use to better inform the media, government and the general public over the rights of a group that comprises 10% of the global population. This research used the Disability Rights Media Monitoring Strategy (DRMMS), see Appendix A for the complete DRMMS methodological approach. This study provides a benchmark from which researchers are able to begin to monitor any change in the media representation of people and issues related to disability to assess if it is evolving and moving towards a more rights based perspective.

Methodology

The sample selected for the study was comprised of a representative group of leading Canadian newspapers: the Vancouver Sun, the Calgary Herald, the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, the Ottawa Citizen, the National Post, the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star, the Toronto Sun and the Montreal Gazette. A sample period of one year was chosen from 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2010. The sample was obtained using a Boolean search of the Nexis Lexus news archive database using a core search string on the terms related specifically to disabilities:1

((Disability or disabled or disabilities or differently abled or handicapped or rehabilitation) and not disabled list).

- Note #1

- Using Google News as a more cost-effective alternative was discussed but was decided against as a sampling resource for this pilot for several reasons. First, the intent was to highlight the most representative media reaching the target population, while Google News only provides digital media content, and does not provide broadcast or print stories other than through their digital equivalent. Second, Google News is not a true news archive, but rather is based on a cache of hyperlinks to digital news sources that exist within a 30-day window, which may have drawbacks in conducting historical searches. Third, the sample of news outlets surveyed by Google is not made public, so it cannot be reliably determined if the outlets chosen by the researcher are actually being cached regularly by Google. Fourth, in order that the results have the property of reliability and replicability, it would be necessary that the same sample be reproduced using the same search criteria at different times. In order to produce a valid sample, it is necessary that all coverage within the parameters set by the researcher be potentially available and replicable. This property is not available using Google News.

- Return

The results from Nexis Lexus were sorted by relevance and the 100 most relevant texts were selected to be examined using CATPAC (Woelfel, 1993). Excluding the root stem terms, the CATPAC program identified a total of 447 terms interpreted to have a significant associative relationship. The 447 terms fell into one of three categories:

-

The associative relationship was solely the result of structure of searching a newspaper archive. For example,

National

andPost

was viewed to have a strong associative relationship, but that is because it is the name of one of the newspapers. Sixty of the terms (13% of the sample) fell under this category. -

The associative relationship was not the result of searching a newspaper archive, but the terms could not be used for the second sampling phase as they were not unique to the issue of disabilities and would generate too many false positives even as applicable items would be caught by the root search. As an example of these results:

lack

andenough

,host

andchallenge

, orinclusion

andexample

. Three-hundred thirty-four terms, or 74% of the sample, fell within this category. - The associative relationship was not the result of searching a newspaper archive and the terms could be used for the second phase as they may be sufficiently unique to the issue of disabilities and may not arise simply from the use of the root search. There were 52 terms, or 12% of the sample, under this category.

Of the 52 terms, 25 were in proximate pairs, while two of the terms (autism

and RDSP

) were not associated with another term. The pairs identified tended to fall into two categories. The first and most common were concordant pairs that might better describe forms of disability or identifiers of people with disabilities, such as disorder

and attention

or down

and syndrome

, or motor

and skills

. A second group of terms formed proper names of people associated with disability topics, such as Howard Levitt, a noted Canadian employment lawyer. The search string employed in the second phase then incorporated these terms in addition to the root search, with the condition that paired the terms must be in proximity to each other (within three words). See Appendix B for the proximate termsm in Nexis Boolean search language.

Items were considered inapplicable if the item did not identify a person with a disability or identify a disability issue. Persons with disabilities included those who have long‐term physical, psychosocial, intellectual or sensory impairments, which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others. The sample also excluded community event listings, indices, obituaries and brief references to disability insurance plans. Inapplicable items comprised almost 72% of the items yielded by the second phase of the search string. This left a remainder of with 3066 applicable items, which comprised the sample, used for analysis purposes.

The sample was coded using three trained coders who were already familiar with disability issues 2. The coding rules were designed to minimize coder opinion. A familiarity with disability topics and issues serves to reduce inter-coder reliability error.

- Note #2

- Students in York University's Critical Disability Studies program.

- Return

The coding instrument was divided into three parts. The first part contained bibliographic variables that included the following: outlet, journalist, date, type of item, section, prominence of mention of disabilities, page, dateline and use of photo (See Appendix B for detailed list). The second part examined the scope of coverage of people with disabilities, and included a question on the form of disability, the source generating the news item about disability issues or people with disabilities, whether people with disabilities and their advocates were given a voice

in the news item by speaking or commenting on the issue rather than a person that does not have a disability summarizing the topic, the use of five key framing mechanisms, and the presence of certain hot-button topics around disabilities, such as the Robert Latimer case in Canada (R. v. Latimer, 2011). The contents of each are again listed in Appendix B.

The third part of the coding instrument focused specifically on the presence of the nineteen rights found in the CRPD. How the media report on issues pertaining to people with disabilities was assessed in terms of the portrayal not only of the subject of the article (i.e., the person with a disability and/or the issue), but also the outcome in the context of how Canadian audiences would see people with disabilities through the lens of the news media 3.

- Note #3

- Students in York University's Critical Disability Studies program.

- Return